Under the Hood: Architecting Real-Time Vehicle Data Streams

Dive into High Mobility's streaming architecture

In this post, I’ll share how the streaming platform is architected in High Mobility platform. My goal is to explain the different parts of the system and discuss the trade-offs and advantages we’ve gained by using this architecture. Hopefully, it gives our customers and partners deeper insight into how the platform works, while also offering potential hires a glimpse into how we approach engineering challenges at High Mobility.

We deliver vehicle data points per day across 27+ brands to our customers. Data delivery isn’t spread evenly throughout the day—instead, we see spikes at different times. We’ve built a scalable solution that not only handles these loads reliably, but also reduces our development time and makes it easy to extend the platform.

If you’d like to learn more about our product and how we work with fleets, you can head over to high-mobility.com. This post, however, is focused purely on the engineering side.

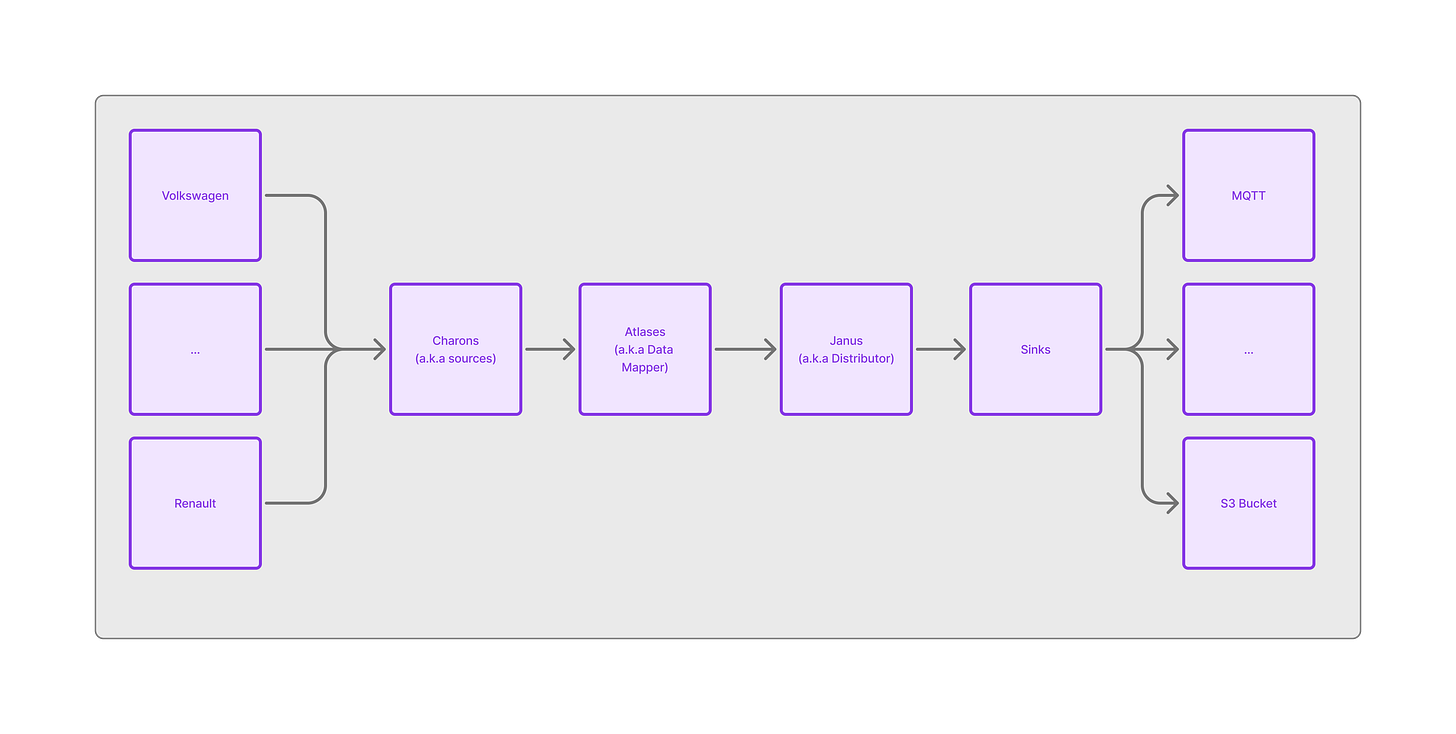

Bird’s-eye view

This system has few components:

Charon: They are responsible for collecting raw vehicle data and push them to our data pipeline.

Atlas: They are responsible for mapping OEM specific to High-Mobility’s AutoAPI format.

Janus: This part is responsible for checking activated vehicles by application and pushing data based on configured permissions.

Sinks: We have multiple sink project which push the data to the desire endpoint that each application has configured.

Components

Before describing each component, it’s worth noting that our data pipeline relies on a Kafka broker. We considered a few alternatives, but in the end in our use case Kafka was the clear winner. The main advantages for our use case are:

Partial ordering: We maintain partial ordering of messages per vehicle, which allows us to deliver data in nearly the same order it was received. Since we changed the data format to send data in bulk (rather than initially sending individual data points e.g odometer), there is ongoing discussion within the engineering team about removing this requirement to alleviate certain bottlenecks—but that remains to be seen.

Data replay: This was the decisive factor. Kafka allows us to republish messages or extract data even after they’ve been pushed to customers. This capability has saved both us and our customers multiple times.

Since we are primarily an Elixir shop, we initially faced some challenges with Kafka implementations in Erlang/Elixir. We’ve contributed back to the community, which has helped us improve Kafka consumption significantly.

Charons

We are consuming data from OEMs using different technologies—such as AMQP, Kinesis, HTTP Push, Kafka, GRPC, SQS and others— and push the messages to our internal broker.

We run around seven Charon Microservices (sometimes referred to as sources), implemented mainly in Elixir, with a few in Kotlin. We’ve kept the Charons as lean as possible: their sole responsibility is to bring vehicle data into our pipeline, without making decisions or inspecting the data.

The only exception is when OEMs don’t provide push technology. In those cases, we’ve implemented a polling mechanism that regularly pulls data from their APIs. Whenever a change is detected, the updated data is pushed into the pipeline.

This project, internally called Charon-Puller, can handle multiple OEM integrations by listening to our event store, identifying which vehicles are activated or deactivated, and starting/stopping API polling accordingly.

Atlases

We run around 17 Atlases, each responsible for mapping raw OEM data to the AutoAPI schema. Atlases are fairly simple projects: at the start of each Atlas, significant research and data analysis are required to achieve the correct mapping. After that, they rarely change, apart from regular maintenance or dependency updates. Since they are stateless and communicate only with our internal Kafka broker, they remain lean and fast.

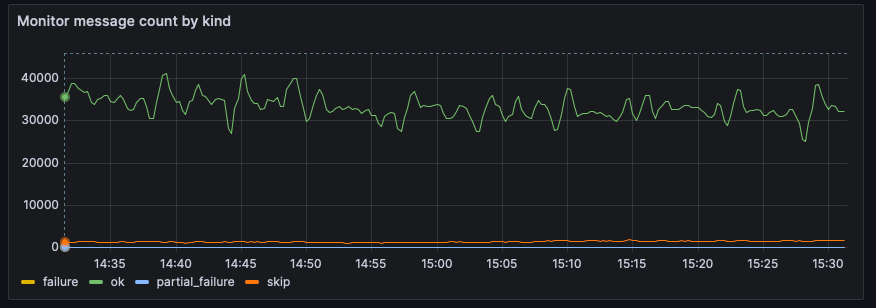

We are monitoring Atlases to understand parsing error rate and other possible issues with data and act on them.

For example, this graph from one of the Atlases, scraped by Prometheus, shows how many messages were successfully processed, failed, or were only partially parseable. We have an alerting system in place that notifies us via Slack whenever a threshold is reached. If a message fails or partially fails, we push it to a DLQ topic, which allows us to review the parsing and resend the data if needed.

Janus

So far, the data pipeline operates without knowing which data belongs to which customer. That changes with Janus. Janus acts as a gateway, determining which customer has requested which dataset, which sink provider they have chosen, and ensuring that only the requested data is passed through the pipeline.

Janus currently gathers this information from our platform. We are in the process of switching it to use our event store.

Sinks

The final part of the pipeline is handled by sinks. We are currently running:

MQTT Sink

Kinesis Sink

S3 Sink

Azure Storage Blob Sink

Each sink listens to the final topic and, if the message is marked for its type, it picks up the message and forwards it to the appropriate destination

It’s worth noting that while High-Mobility maintains the MQTT broker—currently the most popular option among our customers—the other destinations are owned directly by customers. This means customers must configure their AWS or Azure accounts to grant us access to the required resources.

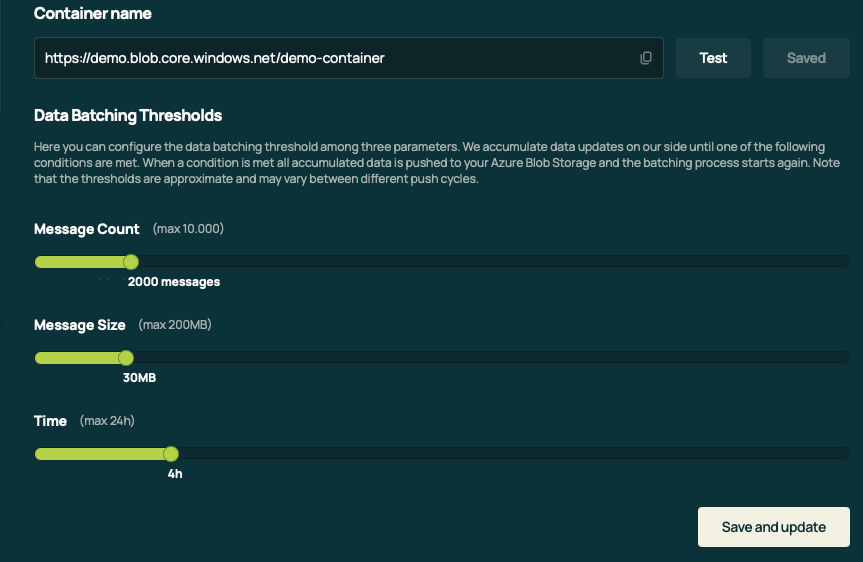

The most recent sink we implemented was the Azure Blob Storage Sink, which offers great flexibility and configurability. As shown in the screenshot below, customers can fine-tune the frequency at which data is flushed into their bucket. This allows them to decide for themselves the balance between data delivery time and data delivery costs, since each push to Azure Blob Storage incurs a cost.

We are also looking into extend this knobs and levers to other Sinks as well.

Conclusion

Looking back at our journey, a few clear lessons stand out:

Keep pipelines small and focused: Simplicity pays off. By breaking the system into lean, purpose-built components, we’ve been able to scale without unnecessary complexity.

Choose the right technology for the job: We’re pragmatic in our stack decisions—for example, using Kotlin for the Kinesis sink where it made the most sense.

Leverage data for multiple purposes: Vehicle data is not just for delivery. We use it for direct Rest API usage(through caching layer), geofencing, as source for answering support cases and unlocking new possibilities across different use cases.